MANCHESTER HISTORIAN: THE WAR ON DRUGS IS A RACE ISSUE - 20/5/2020

On September 14th, 1986, President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan made a national address to declare a ‘war on drugs’ within America. This declaration and the initiatives implemented as a result has directly impacted communities heavily populated with working-class ethnic minorities, the results of which we are still seeing. In this address, the Reagan’s made hyperbolic statements that inflated the extent of drug use in society. By stating that drug use is ‘killing our children’, ‘threatening our communities’ and ‘undercutting our institutions’, the Reagan’s firmly drew a line in public opinion surrounding issues of drug abuse. Those who were for the wellbeing of American society were anti-drug use and anyone who disagreed with their sentiment were pro-drug use, complicit in the demise of American values. Following this speech, public concern about drug use skyrocketed: polling of the American public listing drug use as the country’s number one problem, when, at same time, poverty was steadily increasing, and Reagan was drastically cutting funds to inner-city communities.

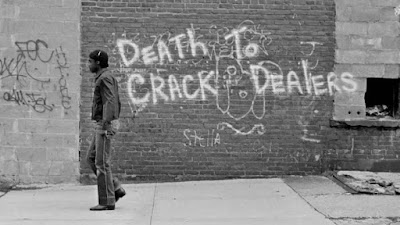

Reagan’s strict political rhetoric throughout his presidency consistently demonised drug use and positioned specific social groups as the perpetrators of this problem. The results of this was felt most by inner-city communities, who were subject to increased police presence on the streets and coercive methods of intervention in order to cease drugs. The arrival of the new drug ‘crack cocaine’ in the mid-80’s caused a national epidemic, and its association with working-class ethnic minorities (specifically those of Black and Latino descent) saw a sharp change in the way drug use was perceived and controlled in American society. ‘Crack’ cocaine is the street name given to cocaine that has been processed with sodium bicarbonate or ammonia thus readily available to be smoked rather than snorted (the most popular mode of consumption). Due to its relatively inexpensive nature and ability to be sold in small quantities as ‘rocks’, crack cocaine was seen as a more lucrative and cost-effective way to consume and sell drugs in comparison to powder cocaine that was comparably more expensive. It is significant to point out here that crack cocaine and powder cocaine have the same physiological composition, rendering their effects virtually identical. However, crack cocaine was policed far more heavily during the 1980’s: its presence in inner-city communities and association with ethnic minorities stigmatised its usage in a way that powder cocaine users did not experience.

Reagan’s introduction of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act (1986) legalised more severe sentences for possession of crack cocaine versus powder cocaine. Known as the 100:1 ratio, this law meant that possession of five grams of crack cocaine was given the same mandatory minimum sentence as possession of five hundred grams of powder cocaine. If you are caught with one gram of crack cocaine you will be subject to the same penalisation as if you were carrying one hundred grams of powder cocaine. As use of crack cocaine was far more prevalent in areas with high populations of ethnic minorities, this sentencing disparity saw the rapid increase of black men in particular in the American criminal justice system. By 1990, the average drug sentence for African Americans was 49% higher than their white counterparts.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act was implicitly racialised. Reagan’s methods didn’t tackle the issue of drug abuse itself, it sought to punish those who took drugs. If you police the drugs more frequently taken by Black and Latino populations, they predominately face the legal penalisation, and become to embody this societal issue.

In addition to this, the Reagan administration approved the increase of police officers and an increase in police powers to use extended force to cease drugs. This led to police officers using more intrusive methods to arrest people, such as raiding people’s homes and using physical violence against civilians in the name of ‘suspicion of drug possession’. These tough on crime policies escalated racial tensions within neighbourhoods, as the escalation of violence saw people resisting arrest and also police officers acting on racial stereotypes to arrest people that they believed were more likely to be carrying drugs without any established evidence. In one particular instance in 1985, a SWAT team used a battering ram to tear into a house they believed people were selling drugs out of. When they entered the house however, they only found two women and three children inside, eating ice cream.

Rates of drug acquisition were often quite low (only 35% of raids actually ceased drugs) proving that most of Reagan’s attempts to solve this war on drugs were fruitless. And as a result, many of Reagan’s initiatives were downscaled by the end of his presidency in 1989. The impact of the Reagan era is still felt throughout America, and the overrepresentation of ethnic minorities in American prisons is now at an all-time high. By publicly labelling drug use as detrimental to the fabric of American society, Reagan instigated a national moral panic, one that called for swift remorseless solutions, rather than offering rehabilitation to drug abusers.

Race relations within America have always been fraught and contentious, and the Reagan era is no exception to this. Disproportionate policing based on racial profiling as well as sentencing disparities have heavily contributed to this and remains a leading factor in mass incarceration today.

By Dara Coker

Comments

Post a Comment